Educational law amendments perpetuate social inequality and increase burdens on families

Press Release

The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) rejects the cabinet-drafted amendments to the education law, which were referred to parliament just days before the end of the current parliamentary term, without serious societal dialogue or consideration of the repercussions these amendments will have on millions of Egyptian families. EIPR believes that the proposed amendments perpetuate inequality and class discrimination and increase burdens on already strained families, thus undermining the goals and mission of education protected by the Egyptian constitution, and which the government itself emphasized in the National Education Strategy and the National Strategy for Human Rights.

The draft education law submitted to the House of Representatives includes the amendment of 17 articles and the introduction of several new texts to the existing law. Amongst the key changes is the extension of compulsory education to include the secondary stage, in compliance with Article 19 of the constitution which stipulates that “education is compulsory until the end of the secondary stage or its equivalent, and the state shall provide free education in its various stages in the state's educational institutions according to law”. The amendments also emphasize the inclusion of Arabic language and national history as core subjects at all education stages. However, the rest of amendments raise many questions regarding the widening of the gap in the provision of educational services, and the growing trend towards privatization of the educational process.

First, Article 9 stipulates that "the Minister of Education and Technical Education, after the approval of the Supreme Council for Pre-University Education, may decide to establish schools with experimental language programs or specialized programs within public schools and license them in private schools… These schools or programs shall be used as a field for the application of new educational experiences in preparation for generalizing them". This amendment opens the door to other - parallel - educational programs and systems, bearing in mind that Egypt already has many different educational systems - English, French, American, experimental, private... etc. - which reinforces inequality in the provision of educational service to students. This discrimination leads to a difference in the quality of educational service, thus deepening the disparity between students, contrary to the constitutional stipulation that education shall be provided in accordance with international quality standards without discrimination.

The imposition of additional fees for registration and retakes in light of the high rates of poverty among Egyptians makes these programs limited to certain groups that can afford them, which would increase the inequality gap between students who can afford the costs and those who cannot. This would undermine equal opportunities and fair competition among students. In addition, families already bear multiple costs related to the educational process, including expenses on transportation, books and private lessons, which increases the burdens and differences between students.

According to the income and expenditure survey issued by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), the share of the top 10% of students in highest-income households from spending on education in 2019-2020 was more than 22 times the share of the bottom 10%. Thus, the introduction of new educational programs for a fee, without taking into account the constitutional guarantee of free education in all stages, and the further privatization of the educational system threaten to exacerbate an already bad situation.

Second, the amendment contained in Article 6 of the draft law stipulates that the minimum pass in religious education shall be raised to 70%, from 50% in the current law. This amendment violates the objectives of education contained in Article 19 of the constitution, which are to establish the concepts of citizenship, tolerance and non-discrimination, as it gives more relative weight to religious education, whose method of teaching at schools is a blatant example of discrimination and sectarianism.

Giving more weight to religious education comes amid a severe shortage of teachers. Thus, there is no sufficient number of teachers to teach religious education, as shown in the complaint of the Qalyubia governorate, for example, which reported that Arabic language teachers exceeded their legal quota of classes taught without pay, as they are not paid for the religious education classes they teach, while some schools are unable to provide teachers for Christian religious education in the first place. There are no teachers dedicated to Christian religious education, thus teachers of other subjects teach it. The faculties of education (at the university level) also do not have a department for Christian religious education. In addition, Christian students are frequently forced to leave their classrooms to the schoolyard that is not prepared for teaching, under the pretext that there are no alternative places.

This amendment may also increase the financial burden on families, as it will likely lead to the creation of a new market for private lessons in religious education, and in return may create a cosmetic process that allows, through leniency in setting questions and awarding grades, to obtain the required percentage.

In this regard, the Toledo Guiding Principles on Teaching about Religions and Beliefs in Public Schools could serve as a standard basis. The Principles stipulate that the teaching of religions and beliefs in public schools should be provided in fair, impartial, objective and scientifically-grounded ways, and that students should learn in an environment that respects human rights, fundamental freedoms and civic values, in a way that helps promote equality, non-discrimination and religious pluralism.

Third, an amendment was introduced to Article 18 stating that "a percentage not exceeding 20% of the overall grade of students of the basic education stage may be allocated to extracurricular activities and participation, and the rest of the percentage shall be calculated for the scores of an examination held in two rounds at the governorate level". In principle, the amendment may not be problematic, but putting one-fifth of the overall grade in the hands of the teacher may open the door to its use against students unfairly, especially in the absence of uniform standards and in light of the wide spread of private tutorship, which would link the obtaining of grades to the off-school relationship and not to the students’ actual academic performance.

Fourth, amendment No. 24 states that "the Minister of Education and Technical Education shall issue a decision regulating retakes for those who failed the exams, including the grades and subjects allowed for retake, and the number of retakes – no less than once in each grade (school year) and twice during each educational stage (primary, preparatory, etc.) – and the dates of these exams and the fees for applying for them, which shall not be less than two hundred pounds and not more than two thousand pounds". Meanwhile, the fees prescribed in the old law were not less than 10 pounds and not more than 20 pounds. The ministry, which cites the small amount, overlooks the fact that more than a third of Egyptians suffer from poverty and extreme poverty, which does not allow poorer students equal retake opportunities and contradicts the principle of free education referenced and protected in the constitution.

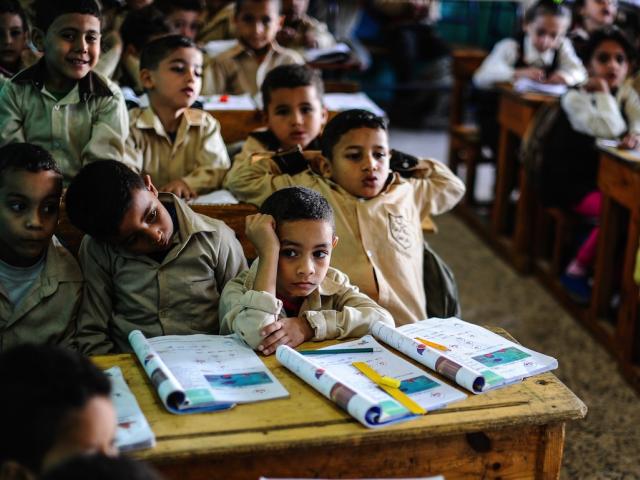

Education is an acquired right guaranteed by successive Egyptian constitutions. The constitution in force affirms that education is free at all stages and that the state is obligated to provide it to all individuals with high quality, in addition to allocating 4% of the GDP to pre-university education and 2% of it to university education. However, the state has not adhered to these percentages to date, thus putting us in a real crisis that threatens any serious attempt to develop or reform the educational system, which suffers from a serious shortage of schools and teachers and overcrowded classrooms.

Education aims not only to qualify students for the labour market as stated in the draft law, but should also help students develop critical thinking, "embed the scientific method of thinking, cultivate talents, and promote innovation", according to the Egyptian constitution. EIPR stresses the importance of developing teachers and raising their standards of living to ensure their ability to perform their tasks efficiently and effectively and to teach the material included in educational curricula in a way that contributes to improving the educational process.