EIPR Issues Position Paper on New Labour Law: We Call on the President Not to Ratify the Law

Press Release

- Benefits included in the law are de facto “suspended”, while its provisions deals severe blows to wages and job security

- Entrenches imbalance between millions of wage workers and business owners and effectively denies workers the right to strike

The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) calls on the President not to ratify the new “Unified” Labour Law, and to return the bill to parliament for further deliberation and revision with the hope of restoring some balance in labour relations—a balance severely undermined by the law in its current form.

EIPR urges Parliament to engage in genuine debate on this crucial legislation involving all stakeholders and the wider public, given the profound implications its provisions have on the livelihoods of millions of Egyptians. Today, EIPR released a position paper titled:

“A Lopsided Law: Impoverishment, Discrimination and Restrictions on Strike in Egypt’s New Labour Law .”

The policy paper characterises the law as a continuation of policies that oppress millions of workers, institutionalise the erosion of real wages, and strip workers of their right to organise, negotiate, and advocate for improved conditions.

The parliament approved the law after an abrupt and rushed tabling and deliberation that is completely incongruent with the gravity of its subject matter, ignoring and violating the accepted legislative process. The draft law was withdrawn multiple times for amendments (by the government) throughout the whole process, and the government submitted incomplete versions to parliamentary committees. Even after the law was initially accepted in principle and was close to full approval, the government withdrew it again to submit further revisions.

EIPR considers halting presidential ratification to be the last opportunity to reconsider the bill in its entirety. The new law exacerbates flaws in the previous legislation and does not mitigate — but rather intensifies — its clear bias toward employers. It undermines job security, offers limited and likely ineffective guarantees for fair wages and bonuses, and removes workers’ last remaining tool of leverage by imposing further restrictions on the right to strike. It also opens the door to arbitrary dismissal and discrimination based on drug use and continues to exclude Egyptian domestic workers from legal protection despite repeated promises to include them under the law, like any other working group.

While the law does include some minor improvements, such as definitions for workplace bullying and harassment, legal recognition for digital platform workers, and protection for female agricultural workers; these articles lack enforceable mechanisms for guaranteeing those rights. An example of how lack of enforceability renders laws ineffective is that the government - despite officially approving and raising the minimum wage - has completely failed to enforce it in the private sector, rendering the whole legislation a law strictly for employers.

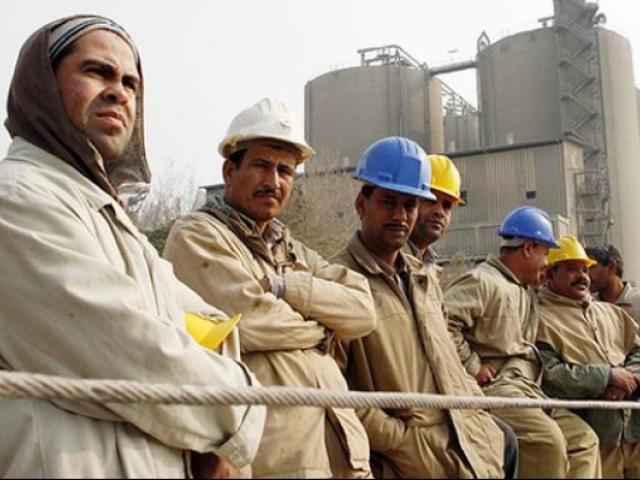

As the law is about to get its final approval, and just two days after it left Parliament, the General Authority for Health Insurance issued a directive stating that women on part-time or daily contracts are not entitled to the breastfeeding hour, typically granted to new mothers to care for their infants. At the same time, dozens of dismissed employees from the Agricultural Bank organised a protest on Sunday, 27 April 2025, outside the bank’s main branch in Dokki, demanding reinstatement. The bank had dismissed around 2,000 employees across various branches and departments without prior notice, none of them being under any form of investigation, even though they held open-ended contracts, with some having over 20 years of service in the bank. Such incidents demonstrably prove the profound imbalance between workers and employers in Egypt, and make it clear that the current philosophy of the law — based on “labour market flexibility” and the open-ended right of employers to hire and fire — deepens inequality and violates the basic rights of waged workers.

In this paper, EIPR proposes several recommendations to amend the law and reframe its underlying philosophy. The recommendations include:

1. Amending the article on the annual bonus in order to tie it to the total wage, indexed to the average inflation rate announced by the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS), instead of setting it the current 3% of the insurance wage.

2. Amending the articles regulating strikes to ensure workers can fully exercise their right to peaceful strike action of all forms, upon notification only, with no obligation to specify an end date. The article permitting strike bans under vaguely defined “exceptional circumstances” should be repealed or amended with the inclusion of a more precise definition of such conditions.

3. Rewriting the articles governing individual employment termination, which currently contain ambiguities and contradictions that enable arbitrary dismissals, effectively reproducing the flaws of the existing labour law.

4. Revising Article 120 to ensure working hours do not exceed 10 hours a day without completely exempting certain categories — such as cleaners and security staff — from all working hours regulations, as is currently the case in the provisions passed by the parliament.

5. Including domestic workers under the protection of the Labour Law, recognising that a significant portion of them already belongs to the informal labour sector which the law already covers. Legal protection should also extend to individuals working without pay for family members who are their primary providers.

6. Extending child care benefits to both men and women, recognising their shared responsibility in family duties. Employers with employees who have dependent children should be required to provide such benefits. The Minister of Manpower’s amendment reducing paternity leave to a single day should be repealed.

7. Amending the article that makes the provision of workplace childcare facilities conditional on employing 100 female workers at a minimum; replacing it with a requirement based on the total number of employees, regardless of gender.

8. Mandatory drug testing should be restricted to specific jobs where it is strictly necessary and in such requirements should be clearly defined in the application process, and likewise for random drug testing.