EIPR commentary on the announcement of a new IMF loan agreement with Egypt

Press Release

The debt crisis will not be solved by a new loan

External debt payments for a year exceed foreign currency reserves and current debt policy is not sustainable

Egypt announced the conclusion of a staff-level new loan agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which would provide financing to partially help the country meet its stressing external obligations. This comes at a moment of crisis, in which the payments of foreign debt obligations exceed, in the short term, foreign exchange reserves, amid increasing difficulties in providing needed foreign currency. At the same time, the value of the pound is facing great pressures, with additional devaluation of the currency being one of the core conditions for the new agreement. The situation reinforces Egypt’s current position as the second largest borrower from the Fund after Argentina, with about 14% of the IMF’s total loans before the new loan.

The terms of the new loan, which becomes effective only after being approved by the Fund's Executive Board, are not specifically known; but the loan will, as usual, be an entry point for obtaining additional loan packages from states, international organizations and markets.

The steady, significant expansion of foreign debt in recent years has played a major role in this crisis situation that the Egyptian economy is going through, as loans have increased steadily during the last ten years and began to accumulate at a higher rate after the signing of the loan agreement with the IMF in November 2016. The rise of the loan’s hard currency service further restricts the economy's ability to meet its import needs of some intermediate goods.

Last June, foreign debt reached $155.7 billion, according to most recent official data released mid October, slightly down from its level in March of the same year, and with an increase of $17.9 billion over the previous fiscal year. Although data on external debt is compiled regularly, its publication has become much delayed in recent years, six months old on average, which often makes the reality far exceed the available data in many cases. The statement released recently on the size of the debt in June was published, but its detailed data has not yet been released.

To deal with the crisis, the government have mainly relied so far on getting more loans, from the IMF, China, and Japan, without linking these loans to development goals that ultimately contribute to improving the economy's ability to finance its activities, and gradually create space to get out of this cycle of resource depletion, in addition to selling productive assets to provide one-off hard currency income.

Increasing Risks

Reports of international financial institutions warn Egypt of the risks of debt, both internal and external, and these warnings are issued even by lending institutions, the latest of which is a recent report by the World Bank published in September under the title “Egypt Public Expenditure Review for the Human Development Sectors”. In the context of its assessment of government social spending policies, the report refers to the problem of increasing debt interest payments, swallowing large part of the public budget resources, so that it “crowds out important productive and social spending.” However, repeated criticisms and warnings have not stopped the increasing borrowing and its burdens.

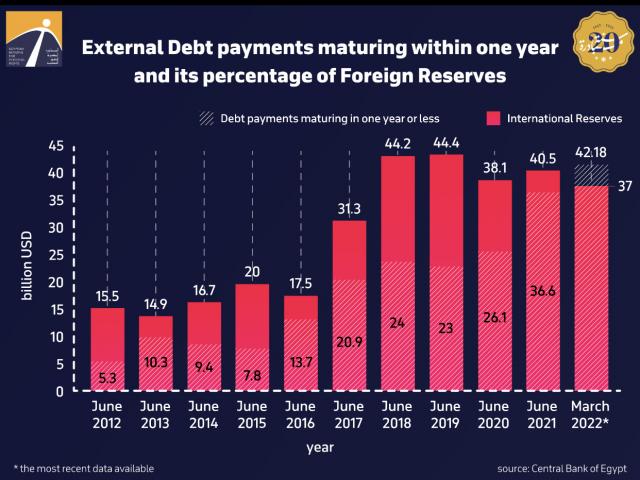

The main weakness in the current situation is that the foreign debt payments maturing in one year or less rose to 42.1 billion dollars last March, according to Central Bank data, exceeding the value of Egypt's foreign exchange reserves that stood at 37 billion dollars in the same month. We should take into account that foreign exchange reserves should cover Egypt's various obligations, primarily imports, as well as debt service and other external needs. At the same time, the size of reserves has been declining over the past months, reaching $33.1 billion at the end of September.

It is interesting to note that before the start of the policy of expanding external borrowing that the state resorted to during the last decade, the foreign exchange reserves covered the total external debt, as the reserves in June 2010 amounted to about 35 billion dollars and the total external debt was 34 billion dollars.

Devaluating the pound increases pressure

The pressure represented by these debts is mounting with the continuous decline in the value of the local currency, as the pound has lost since last March until now about 25% of its value, and is expected to decline further in the coming months, as most expectations indicate.

The fragility of this tense situation is deepened by the fact that one of the sources of hard currency on which the state has relied during the past years is based on another type of debt, which is through foreigners buying government securities. This type of short-term debt, attracted by high interest rates, is by its nature fast-moving and highly sensitive to global conditions.

Thus, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and with the US interest rate hike, about $20 billion in investments in government debt instruments exited Egypt. This sudden exit has put a huge strain on the limited dollar resources, and thus exerted further pressure on the value of the pound.

The continuous decline in the value of the pound increases the burden of external debt on the economy. This can be seen by tracking its equivalent value in Egyptian pounds. The volume of external debt last March amounted to 157.8 billion dollars, which was equivalent to about 2500 billion pounds, before the decline in the exchange rate of the pound in late March. Then, its value increased before the end of the month to the equivalent of about EGP 2,900 billion (an increase of more than EGP 400 billion), after changing the Central Bank’s policy towards the exchange rate, allowing a gradual devaluation of the pound, leading the local currency to lose about 14% of its value against the dollar by March. Although the external debt declined by about $2.1 billion in June compared to March, its equivalent value in local currency rose to 3067 billion Egyptian pounds, according to the current exchange rate of the pound against the dollar, which will negatively affect indicators such as the budget deficit and the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Estimates indicate that the exchange rate would reach at least 23 pounds a dollar when the agreement is concluded with the Fund, which would bring the value of the external debt to the equivalent of 3581 billion pounds, before adding the additional debt since then till the signing of the new loan agreement.

Crowding out development and public services

Although external debt and dependency on foreign finance as a financing mechanism represents greater pressure on state’s resources, as it places more burden on external balances (since it requires it to provide hard currency to pay its obligations), the state’s deepening reliance on debt in general as a main financing mechanism, year after year, is increasingly leading to a reduction in spending on key development areas.

Looking at the state budget for the current fiscal year 2022/2023, the repayment of domestic and foreign loan installments occupied about one-third of total public expenditure, which includes all state budget spending in a year (expenditures, asset acquisition and loans repayment). The value of the loan repayment provisions reached 965 billion pounds.

As for the debt interests (domestic and foreign), the state allocates an additional 690 billion pounds, bringing the total amount allocated by the state to repay loans and their interests to about 54% of its total expenditures in the current fiscal year. This crisis situation, which narrows the space for public spending on various areas of benefit to citizens, calls for a reconsideration of policies that rely on debt as a main source of financing.

However, the budget itself shows that the state’s plan to generate revenues, needed to cover this year’s expenses, remains mainly based on debt, as domestic and foreign borrowing represent half of the revenues that the state intends to collect in the current fiscal year.

Borrowing is not supposed to be a goal in itself, but it is an option among several options, to provide the required financing to meet some urgent needs for which there is no available financing, or to spend on developing economic activity that generates greater return than the value of the loan. Borrowing should be part of a clear plan to develop certain economic sectors, in a way that enhances the economy’s ability to grow and create a surplus that spares it from spinning in the cycle of loans.

The IMF, which just agreed with Egypt a loan similar to the one it provided six years ago, had predicted, within the framework of the previous financing agreement, accompanied by an “economic reform” program agreed upon between the two parties, that the rate of economic growth would rise, and dependence on debt would decrease as a result of implementing the program and as “investments and exports” become drivers of growth replacing debt-financed consumption. However, this prediction was not fulfilled. Rather, dependence on debt worsened after six years, so that a new loan from the Fund became the only lifeline again, a situation that is likely to recur and deteriorate further if there is no real reconsideration of the borrowing policy.

EIPR closely monitored the status of the external debt and warned against the policies of debt dependency over the past years. We recall here some of the recommendations included in the annual reports issued by EIPR on external debt since 2016, which are still far from being realized despite their urgent necessity:

-

The necessity of adopting more transparency, oversight and accountability over aspects of debt expenditure, which are increasing annually, so that they can be directed to meet development needs. Despite the amount of government data available, it is noted that it is more and more characterized by inconsistency, lack of coherence and irregular publication, which all reflect a lack of transparency.

-

The necessity of placing the external debt dossier under the supervision of Parliament (as stipulated by the Constitution), so that there would be no external loans without the approval of Parliament, whoever the borrower is, provided that a payment plan and a plan for the use of funds are presented.

-

Development of a publicly available five-year plan for the projects to be financed by external borrowing, and a parallel plan for developing dollar resources that allow repayment, to be approved by Parliament through legislation. The government should be held accountable for the degree of its commitment to that plan.

-

The necessity of starting a general debate over the trade-offs of external and internal borrowing.

-

Setting a legal ceiling for external borrowing as a percentage of GDP (It existed in Mubarak’s era without legislative commitment).

-

Restructuring the tax system to become more pervasive and just, which would provide sustainable resources for the budget and redistribute burdens fairly on the rich and the owners of wealth and rentier non-productive activities.

This commentary was prepared by Maye Kabil, senior researcher in the Economic and Social Justice Unit at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.