How much are Egyptian citizens paying because of arbitration cases?

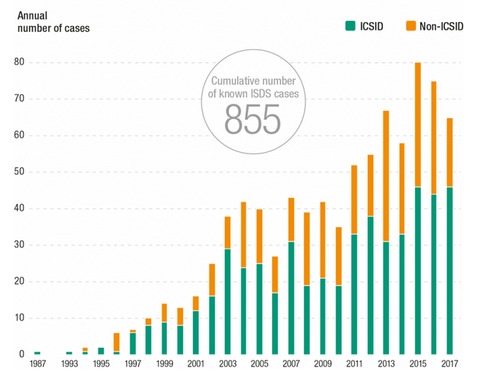

Egypt currently has 32 cases pending against it before the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), part of the World Bank Group, putting it in the top five globally after Argentina, Venezuela, Spain, and the Czech Republic1. The most recent suit was filed on September 19, 2018.

The number of claims made against Egypt increased sharply after 2011: 19 cases were filed against the Egyptian government in just five years from 2011 to 2016. Most of these are seeking compensation for measures taken by the Egyptian government or judgments issued by the Administrative Court pertaining to Mubarak-era corruption and shady deals.

Before the revolution, Egypt did not lose all arbitration suits, but post-revolution it has tended to seek settlements with investors, the terms of which are not officially released. According to available information, Egypt paid out $224.2 million and LE42 billion in compensation for all three cases resolved in favor of investors before 2011 as well as later settlements made to avoid international arbitration. This amount—what is known—is the equivalent to roughly half of the revenues from the Suez Canal in 2016/17 based on current dollar prices.

Again, the figures involved in some settlements are unknown, so this sum includes only verified compensation. (For more background on arbitration cases against Egypt, see “Investment Against Justice” an EIPR report from 2016.)

What is international arbitration?

International arbitration is a system for adjudicating disputes between states and investors that as an alternative to the ordinary national judiciary. It thus distances corporations from the numerous conflicting laws in each state and ostensibly protects the investments of individuals and companies from biased, immature, and at times corrupt local courts.

Critics say this system comprises a complex network of interests that favors investors and functions as a massive industry controlled by a narrow elite of arbitrators, lawyers, and legal consulting firms, which rack up millions of dollars in fines and litigation fees paid by states out of the public treasury.

Legal consultants and brokerage firms take every opportunity offered by economic crises and political shifts in various countries to urge investors to take action against ailing governments and others that institute reforms in response to popular demands. These firms played a substantial role in reining in governments in Greece, Egypt, South Africa, Argentina, and Germany after encouraging investors to use international arbitration as a form of political pressure.

But why does Egypt abide by international arbitration? The answer is BITs

Bilateral investment treaties (BITs)2 are agreements between two states that offer guarantees and privileges to investors with the aim of protecting the investments of companies registered in one country in the territory of another. These treaties guarantee the right of recourse to international arbitration as a basic condition and the sole means of resolving disputes that may arise between the investor and the state.3

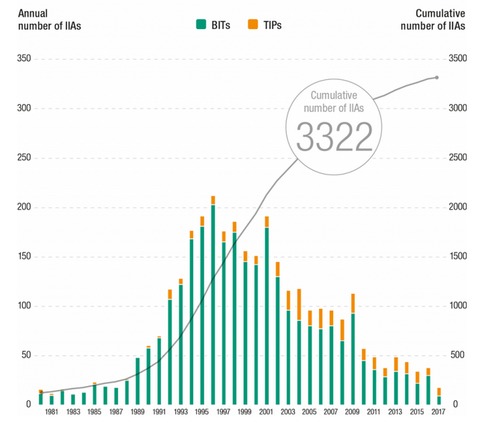

These treaties are the most common type of investment agreement between states, particularly with the aim of encouraging investment in developing countries. Their use became widespread in the 1990s, with 2,946 such treaties having been signed worldwide as of the end of 2017.4

Various Egyptian governments had signed 113 investment treaties as of the end of 2014, 100 of them BITs. In the 1990s, following a September 1991 agreement with the International Monetary Fund for an Economic Reform and Structural Adjustment Program, Egypt signed 69 BITs.5

The most recent, biggest fine against Egypt: why?

Union Fenosa Gas punished Egypt because it failed to provide natural gas to the company after the revolution, when the government was forced to use the gas to meet local needs, particularly for electricity.6

In the suit it filed against Egypt in February 2014, Union Fenosa cited the BIT signed between Egypt and Spain in 1992, which, like other bilateral treaties, provided for the right of “fair and equitable treatment.”

Fair and equitable treatment is a set of loosely defined terms in BITs that guarantee “the legitimate rights of the investor to national treatment”—meaning the right to have the host state treat him as a local investor or government sector. This bars the granting of any privileges to others that the foreign investor does not also receive, although it does not preclude special privileges to foreign investors. Equitable treatment also includes the investor’s right to receive the same treatment as all foreign investors of all nationalities. In fact, an investor of any nationality has the right to sue a host state based on what it offers to other investors of other nationalities through BITs with their states.

Egypt was hit with the biggest fine in its history when the ICSID ruled on September 3, 2018 that Egypt was liable for compensation of $2 billion to Union Fenosa, as damages for the 2014 government’s failure to provide gas to the company during the energy crisis in Egypt. The Egyptian government is expected to pay the fine in the equivalent value of natural gas.7

Egypt is also facing another fine of up to $2 billion in another case pending with the East Mediterranean Gas Company and the Israeli electric company due to interruptions in gas supplies in 2012 after repeated bombings of the pipeline.8

What is the most equitable alternative for developing states?

International efforts to reconsider the BITs as a model have reached a real turning point. A new generation of agreements signed 2017 include different terms that make them diametrically opposed to the old BITs and are in keeping with the set of reforms proposed by the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), most importantly9:

1. Protection for the right of regulation in order to achieve sustainable development goals and balance the protection of investment with the public interest, and assurances that the investment agreements will not encroach on state sovereignty or the state’s right to design public policy and pass laws. These reforms involve a reconsideration of protections included in BITs, such as the right to fair and equitable treatment.

2. Environmental and investment obligations prior to investment, to support states’ ability to achieve development, protect their right to regulate their affairs, and avoid arbitration by agreeing on prior commitments.

3. Guarantee of responsible investment, meaning investment that does not adversely affect or contradict health, the environment, labor rights or human rights in general, or any other public interest. BITs currently in force carry no such responsibilities and do not include terms guaranteeing environmental and economic justice.

4. Reform of the investment dispute resolution order, which includes two options: 1) make recourse to international arbitration more onerous while also reforming the system, making it more transparent, adding new elements such as a jury panel, and strengthening the role of the local judiciary by establishing specialized economic courts; or 2) end the current system in full and replace it with a standing international court to settle disputes.

Have developing states learned the lesson? Has Egypt?

Developing countries have begun retreating from the BIT model. The World Investment Report 2018 issued by UNCTAD noted that fewer investment treaties were signed in 2017 than in any year since 1983, with only 18 agreements, 9 of them BITs. And for the first time, the number of agreements repealed (22) was greater than the number signed.

In February 2015, India, Brazil, and Norway presented new models of BITs in a meeting of the UNCTAD experts’ group on the transformation of international investment agreements. India brought the new model into effect in February 2016. In 2011, the Australian government declared that its investment and trade agreements would no longer guarantee the right of international arbitration. Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela also cancelled several BITs and seceded from the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States, which established the ICSID.

This is all part of an international reassessment that began earlier. Since 2012, more than 150 states have taken action to reconsider BITs signed prior to 2010, in a drive toward fair investment treaties that achieve sustainable development goals (see the World Investment Report 2018).

As for Egypt, it has been slow to join the trend of reconsidering investment treaties and the international arbitration system, which means its citizens must shoulder the costs—billions in addition to old debts, as their rights to public spending are further eroded. The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights recommends adopting the principles of UNCTAD’s roadmap on BITs and international arbitration, which more than 150 countries have begun following in order to protect the goals of sustainable development.

Figure 1: Number of investment agreements signed annually worldwide

Figure 2: Number of international arbitration cases worldwide

- 1. For the number of cases filed against the Egyptian government with the ICSID, see https://icsid.worldbank.org/en/Pages/cases/AdvancedSearch.aspx.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2018, http://worldinvestmentreport.unctad.org/world-investment-report-2018/cha....

- 5. See fn 1.

- 6. Aswat Masriya, Feb. 19, 2015, http://www.aswatmasriya.com/news/details/36880.

- 7. Financial Times, Sep. 3, 2018, “Egypt to pay Spanish-Italian JV $2bn in natural gas dispute,” https://www.ft.com/content/0d0dfd96-af6c-11e8-8d14-6f049d06439cFinancial.

- 8. Shorouk, Feb. 27, 2018, https://www.shorouknews.com/news/view.aspx?cdate=27022018&id=d04ad2a4-1e....

- 9. EIPR, 2016, Investment Against Justice (Arabic), https://eipr.org/sites/default/files/reports/pdf/investment_against_just....